In Praise of Mr. Steinberg

Comics critic Domingos Isabelinho recently took the comics blogosphere gently to task for not noticing a central influence on Mazzucchelli’s landmark Asterios Polyp: the art of Saul Steinberg.

Comics critic Domingos Isabelinho recently took the comics blogosphere gently to task for not noticing a central influence on Mazzucchelli’s landmark Asterios Polyp: the art of Saul Steinberg.

It’s true. I failed to mention Steinberg in my own review of AP, but now that Isabelinho has pointed it out, it’s hard not to see.

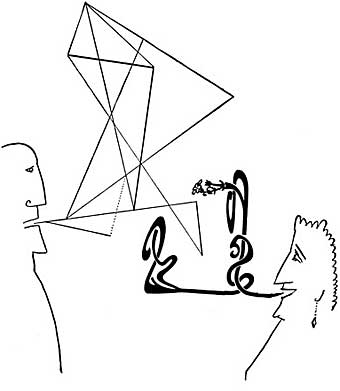

I always loved Saul Steinberg’s work and was influenced by him myself at an early age, though it might be harder to spot in my work. Of all the cartoonists whose work I’ve enjoyed, no one else was as comfortable to wander the big triangle in search of a visual idea.

It was liberating for a draftsman with limited gifts (that would be me) to understand that art could communicate the way written language does, while simultaneously flirting with both resemblance and abstraction.

Steinberg’s art made the possibilities of the picture plane look near and accessible to anyone in the mood to pick up a pen. And so they are.

hmm. I never read Asterios Polyp myself, because I’m currently stuck on comics from the 80’s and 90’s and whatever else is in my dad’s 6 comic boxes. I had to convince myself not to read Zot! again so I could start on The Spirit, Kings in Disguise, and Tales of the Beanworld.

Scott, I’m writing about models (in the context of Danto’s “Artworld”) and I put your big triangle, along with Mary Kuhner’s threefold model for role-playing games, in a category of n-polar models. (I guess three is the number you’d go to because three points define a plane and an n-polar system of more than two dimensions would be hard to visualize.)

I contrast that model with my preference, an n-dimensional cartesian map of axis with varying orthogonality. Because sometimes some images are firmly anchored in more than one pole at a time.

Actually, the same goes for the four jungian camps in Making Comics—in that case, a four dimensional cartesian system and it would be possible to score pretty high on all four axes, in theory.

It certainly is possible to score low on them.