Wrong Question?

Related to yesterday’s post, there’s a controversy brewing over whether video games are “Art” or not, spurred on by various comments by film critic Roger Ebert.

A couple of people have even Beetlejuiced* me, wondering which side of the issue I’d come down upon. Anyone who’s read the art chapters of UC or RC can probably guess my response.

If you’re asking if videogames are art, I think you’re asking the wrong question. I don’t think art is an either/or proposition. Any medium can accommodate it, and there can be at least a little art in nearly everything we do.

Once in a while, someone makes a work in their chosen medium so driven by aesthetic concerns and so removed from any other consideration that we trot out the A-word, but even then it’s a matter of degrees, and for most creative endeavors you can find a full spectrum from the sublime to the mundane.

The idea that for the lack of a single brush stroke or word balloon or camera angle, we could consign something as complex as a painting or a graphic novel or a motion picture to the art equivalent of Heaven or Hell does a disservice to the depth and breadth of those forms. There’s no hard dividing line, no thumbs up or thumbs down for these things.

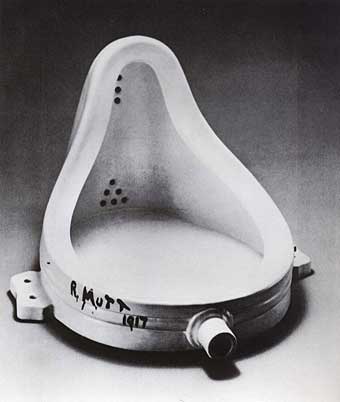

Games are an interesting case though. Duchamp insisted that the viewer is a contributor to the creative act, and on several levels actually completes the work. In games, that “user interaction” is more than just a contribution to the work—it’s the very substance of the thing. The idea of abdicating authorship to the user (a concept I first heard about from game designer Doug Church) gets pretty close to the DNA of all games.

Does “abdicating authorship” mean abdicating any hopes of high art though? I don’t think so. But what do I know? I make comic books.

“I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.” –Marcel Duchamp

As a theatrical designer, I would argue that abdicating authorship in favor of collaboration bolsters rather than threatens video games’ artiness.

I think I may have been the first commentor to mention you. I was also of the opinion that the wrong questions were being asked. I also remembere Marcel Duchamp, but off-line at a cocktail party in conversation about the article.

I’ll be re-editing the blog post I wrote last night to Beetlejuice you yet again.

I really hope the trend of Beetlejuicing Scott continues. I like the idea that he is someone that can be conjured…

How much abdication is really done, though? Aren’t all eventualities designed into the game all ready? Are there many or any games that can create a new addition without input from the designers? And is the ‘art’ of the game totally in what the gamer sees or in how it’s put together, how the computer interacts with data, etc.? I’ve heard from some coder friends that coding is itself an artform generally unappreciatable as it’s so rarely seen.

The skills of the given gamer (or willingness to find cheat codes, etc) only determine the amount of the whole game said gamer will see. Games are unique as an artform in this respect as far as I can tell. That they’re art isn’t a question; you’re totally right there.

As video game/comics blogger, I thought about weighing in on the numerous posts and articles on the controversy by Beetlejuicing you too. In the end, though, I just kind of felt Ebert’s comments were so narrow minded that they didn’t need to be challenged–just like I don’t argue with 5-year olds about whether or not Superman is the best superhero 😉

Video games are a collaboration of many different forms of art into one (hopefully) cohesive, interactive package. Video games are absolutely art.

As a videogame professional, I find it more interesting to debate whether movies will ever meet my definition of good interactive gameplay. Stop worrying about whether a game has made you cry – Has a movie ever made you feel rewarded for a decision you made?

And Ben V – You really should try arguing with 5 year olds about whether Superman is the best superhero. It’s fun.

Myst and Riven moved me more than a lot of movies I’ve seen… 🙂

I’m in a post-C2E2-post-travel zombie state but seeing Fountain on your blog made me smile.

Later I’ll read why it’s there

Until then there is always this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUYovIM8WQc

The thing I always worry about in the games/art debacle is whether games are protected free speech and should be treated as such.

I love Ebert’s commentary on films; his commentary on games tends to make me shudder. I think I’d be quite interested to hear his commentary on ready-made urinals.

I don’t think Ebert’s so much narrow minded as he is committed to a romantic idea about the role of artists as intellectual heroes. I’m also not sure he means to disparage games by saying they’re not art. He just means that authorial control is an integral part of the question of art, and that puts games in a different category.

Of course, Ebert should know better than most that no single person has complete authorial control over a movie, either. We consider nearly every person involved in the production of a film to be an artist in some sense, and so far as the director is the “real” author, it’s only because he’s corralled all the others into cooperating. Artists can collaborate and still make art; why can’t the audience enter into the partnership too?

To quote the man:

“[V]ideo games represent a loss of those precious hours we have available to make ourselves more cultured, civilized and empathetic.”

He absolutely means to disparage games. Though he doesn’t seem to know much about them.

Well Fraser, I guess it just goes to show that Ebert, like many of his generation, doesn’t understand video games. Imagine that!

I think those of us who enjoy video games are a little insecure about the artistic credentials of our medium. Beyond the frat-boy set, many of us actually get a kind of personal edification from playing games, the kind of thing you’d hope to find in a movie or a book or what have you. Other times we come across things that are simply beautiful. If we really think about it, there’s no question: putting aside the question of whether all art is beautiful, how can people make something beautiful and not call it art? Ebert can’t see the beauty, either in the graphics or in the playing process itself, or if he does he still thinks it’s something different.

Really, it comes down to being stubborn. People have wasted at least as many hours watching bad movies as playing games. Ebert would surely admit that, but he’d probably come up with another rationalization, since he’s stuck playing this role now.

It’s arbitrary what is art and what is not. This term can be expanded on everything and also limited to such an extent that not even the term “art” itself is art.

But there are certainly cultural norms that have shaped the perception of what art is (not that I necessarily agree with them).

1. Separation from practical life. (The perception that art should fulfill something beyond the survival instincts.) This separation is often done simply by naming the product as art–put it in a museum and…viola! It’s art!

2. Like-ability. People who are offended by Chris Ofili’s “Holy Virgin Mary” (the one where she’s covered in dung) don’t call it art. I really disagree with this type of thinking, since a cake is still a cake even if you don’t like the taste, but it is a fairly common paradigm.

I also think sometimes people need to step back and consider what they are doing when they define something. For example, when Scott “Defines” comics, he doesn’t do it to limit what they can be, but rather to identify discrete characteristics to better understand connections across a spectrum of media. By focusing on the presence of closure in sequential pictures, it actually expanded what many considered to be comics.

In general, I’m in favor of this kind of “Defining.” It should be done as a critical tool to help us understand what we’re looking at. I get the feeling Ebert is using it as a way to say one thing is “better” than the other.

Personally I hate the “Does __ make __art” conversation. It’s really useless. Because we don’t learn anything new about the things we fill the blanks with. At the end of those discussions all we have is the arbitrary concept that ‘Something’ is or is not art. Will knowing whether or not video game designers are artists or not change the way they make games? Not really. If the general consensus decides they are not artists, that doesn’t mean there won’t still be incredibly driven, creative designers looking for knew ways to engage audiences. And if they decide they ‘are’ artists that doesn’t mean there won’t still be countless unimaginative drones designing boring games just to pay the rent. “Art” is just a word.

Ah, but as long as people have faith that there is such a thing as “art”, video game developers have three choices. They can believe that:

A. Nothing they ever do will earn them that coveted label, demeaning them in the eyes of society (the Ebert option).

B. Everything they do is now anointed as “art” regardless of how crappy and shallow it is (the smug, circle jerk option).

C. Every day is an opportunity, in some small way, to strive for something beyond just filling shelf space.

I would insist that “C” is the most constructive, grounded, and forward-looking way to look at what a creative individual does, and reason enough to engage in the discussion.

Can I quote you on that? 🙂

Sure, why not?

I think current movies, as confined as they are by commercial viability, have to argue just as hard to climb the ivory tower as games do. It’s easier to get an indie game made and played right now than it is to get a real independent movie distributed and watched.

I defy anyone to play something like Ico and not recognize video games as having the potential for being “high art”.

All art is a collaboration between the artist and the viewer, mediated by the work of art. Games do not lose artiness simply because of the collaboration.

I like (C), too.

I meant to surround the first two sentences with a “pontificate” tag, but your site doesn’t like tags. At least not the way I wrote them.

Actually, you can’t see it, but the whole blog is bracketed by the pontificate tag. New feature in HTML 5.

^__–

I honestly have to wonder whether or not Ebert understands irony or even the fundamentals of critical analysis if he feels audience interpretation has nothing to do with observation. Sola Scriptura does not apply to art.

On a more important note, I think one of the great advantages of a video game is a sort of compartmentalised narration. Global events can be taking place in a linear fashion while the player initiates sub-plots or dialogues in a sequence they’re comfortable with. Life bars, ammo gauges, inventory screens can hover around or pop up and, just like a panel transition, the player connects the pieces together on the fly to connect them to the overall narrative. You can poke around for details to flesh out the story or perhaps you might continue on the main track to keep up the pace and strike while the emotional iron is hot. These are things a game can do which other media can’t do quite the same way, but if anything comes close to your ideas of comics which can be read in nearly any sequence, it would be games.

[…] Scott McCloud of Understanding Comics fame weighs in. […]

[…] Ashcraft also chimes in with a good response. If you were following, you might have missed this really good response from the esteemed Scott McCloud. The whole thing is worth reading but here’s an excerpt: […]

[…] Read full story […]

[…] to MassArt, pointed me in the direction of the wonderful and brilliant comic artist and scholar Scott McCloud, and his omnibus art history book, Understanding Comics. And in that book, I found the answers […]