It took about 3 minutes in the mid-’90s for comic strips to take to the Web; like those newborn babies dropped in water that instantly know how to swim. If an online comic strip looked like its printed cousins, it was just as readable. If surfers had short attention spans, no problem. The Web was one big refrigerator, covered with magnets, waiting for something short, funny and recognizable to snap on to its audience.

Long form comics (the online equivalent of comic books and graphic novels) have had a harder road to follow. Fewer readers have the time or stamina for a web-based Maus or Watchmen during precious coffee breaks at work. And long, serious comics don’t always lend themselves to the kinds of conspicuous ads and light-hearted merchandise that have kept many daily strips afloat. Still, if a young artist is passionate enough to create a long form masterpiece they won’t let these limitations stop them and sooner or later they’ll find an audience.

But there’s one more obstacle, which is far more infuriating because it’s so pointless and unnecessary: The page designs of most long form webcomics suck donkey dick. Good artists and writers—including some of my favorite cartoonists in the world—force readers to sroll, then click, then read, then scroll, then read, then click, then scroll again for no other reason than a stubborn belief that all comics pages have to be taller than wide, and that all web pages need a metric ton of blinking crap at the top to work.

Long form comics are different from strips. If a cartoonist wants their readers to stick with a 60-page story about their Moroccan grandmother’s struggle with Diabetes, they need that reader to lose themselves in the story. That means keeping readers’ eyes on the page. Every time a reader looks away to navigate, they’re leaving the world of the story, and returning to the world of scrollbars and links.

The simplest solution—choosing screen-fitting pages and putting them near the top of the screen—is not rocket science. Charlie Parker’s Argon Zark did it over a decade ago (screens were smaller then), Justine Shaw, the first webcomics artist ever nominated for an Eisner, created a near-perfect format with Nowhere Girl in 2002 (making the entire page a next button), and Larson and O’Malley’s wonderful Bear Creek Apartments from 2008 had no trouble getting thousands of readers to click to the end.

But still the madness continues, and every day another dozen artists put their comics online using a format every bit as a annoying as a TV show that automatically changes channels every 3 minutes, while a four year-old stands directly in front of the screen, screaming the theme from Barney.

Which brings us to Yves Bigerel.

A lot of people have been pointing me to Yves’ two webcomics about webcomics over the last couple of weeks. If your own attention spans aren’t too taxed already, I hope you’ll consider reading both now from beginning to end (should only take about 6 minutes, they’re not too long):

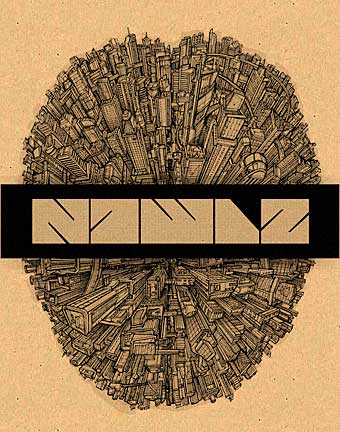

About Digital Comics

About About Digital Comics

Now, there are about a dozen issues raised in these comics that I’m not going to touch on. He’s actually heading in some directions that I’d be reluctant to go. But there’s no question that these comics struck a chord with artists and readers in the last few weeks, including me. And I think that one of the most refreshing aspects (“refreshing” as in a cool drink of water after five days in the desert) is the fact that navigating using Yves’ system is as simple and intuitive as breathing.

If that’s the message more cartoonists take to heart in the coming months, we may see some progress yet.